What Exactly Are Impetigo and Cellulitis?

Impetigo and cellulitis both start with a break in the skin - a scratch, a bug bite, a crack from dryness - but they go in very different directions. Impetigo is a surface-level infection, mostly affecting kids. It shows up as red sores, usually around the nose or mouth, that turn into blisters, burst, and then form that sticky, honey-colored crust. It’s not just ugly - it’s contagious. If your child has it, they can spread it to siblings or classmates in minutes through shared towels, toys, or even a quick hug.

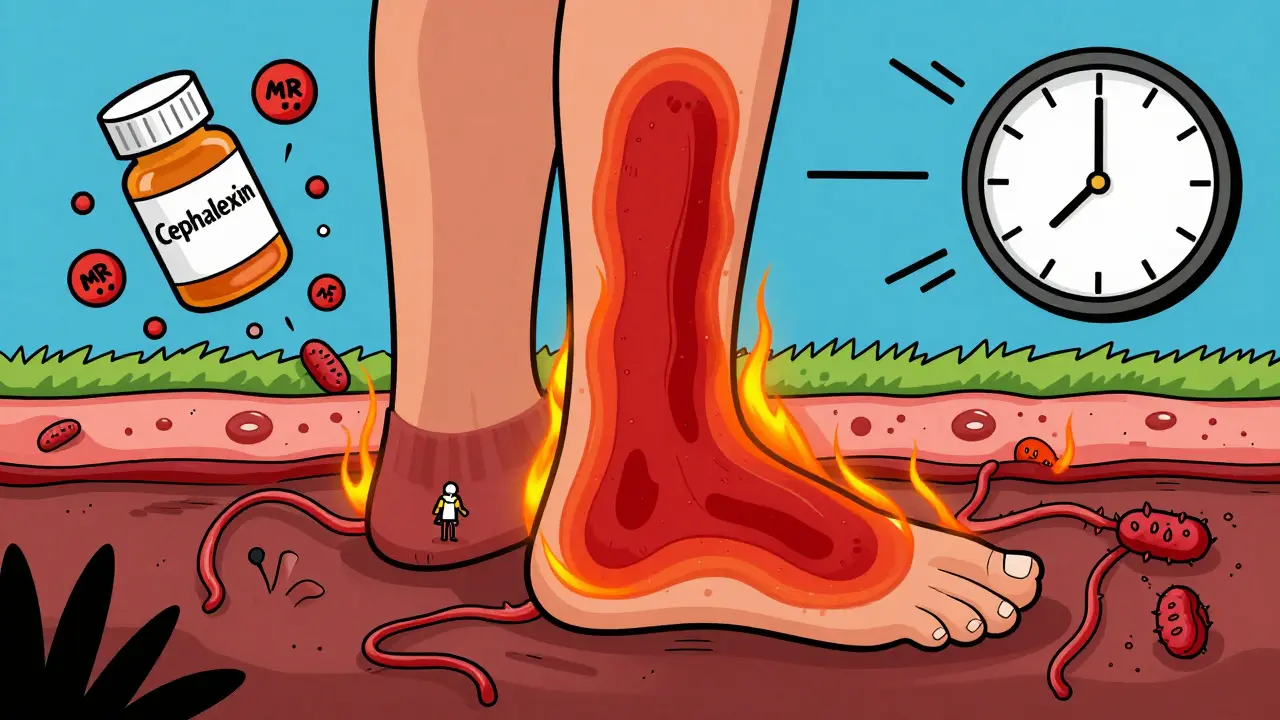

Cellulitis is deeper. It doesn’t sit on top of the skin. It sneaks in under it, spreading through the fatty layer below. The skin turns red, hot, swollen, and painful. The edges don’t have a clear line - it just keeps spreading. You might not even remember how the skin got broken. A tiny cut from gardening, a fungal infection between the toes, even a razor nick can be the starting point. Unlike impetigo, cellulitis isn’t passed from person to person. It’s your own bacteria, usually from your skin or nose, finding a way in and multiplying fast.

Why the Bacteria Have Changed - and Why Penicillin Doesn’t Work Anymore

For decades, doctors thought impetigo was mostly caused by Group A Strep. That’s what textbooks said. But over the last 20 years, the bacteria changed. Today, around 90% of impetigo cases are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, either alone or mixed with Strep. And here’s the kicker: almost all of these staph strains make a special enzyme called penicillinase. That enzyme breaks down penicillin like it’s paper. So if your doctor still prescribes penicillin for impetigo, it’s likely to fail - studies show about 68% of cases won’t improve.

This shift matters because treatment depends on knowing what you’re fighting. Topical antibiotics like mupirocin (Bactroban) work great for impetigo because they hit the surface bacteria hard. But if you use the wrong antibiotic - say, one that only targets Strep - you’re leaving the staph untouched. That’s why the American Academy of Family Physicians updated their guidelines in the early 2000s and why current guidelines from the Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic now recommend mupirocin or retapamulin as first-line treatments for localized impetigo.

How Impetigo and Cellulitis Look Different - And When to Worry

Impetigo usually looks like a cluster of small, red spots that turn into blisters, then crust over. The crust is the giveaway - it’s thick, golden, and sticky. It’s most common on the face, especially around the nose and mouth. In kids under two, you might see bullous impetigo: big, fluid-filled blisters that pop easily, leaving raw patches with a ring of leftover skin around them. These are less common but still manageable with oral antibiotics.

Cellulitis looks nothing like that. It’s not a blister or a crust. It’s a patch of skin that looks like a bad sunburn, but it’s warm to the touch, tight, and tender. It spreads. If you draw a line around the red area today and it’s bigger tomorrow, that’s a red flag. It most often hits the lower legs in adults. In kids, it’s more common on the face or arms. The key difference? Impetigo is shallow. Cellulitis is deep. And that’s why one can be treated with a cream and the other needs pills or even an IV.

Watch for danger signs. If you or your child develops a fever over 38.3°C (101°F), the red area spreads faster than 2 cm per day, or the skin looks like it’s peeling off like a burn - call an ambulance. That could be staph scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), a rare but deadly toxin-driven reaction mostly in babies. It’s not common, but it kills 2-5% of cases even with treatment. Don’t wait.

Antibiotics: What Works, What Doesn’t, and What’s New

For mild, localized impetigo, mupirocin ointment applied three times a day for five days cures 90% of cases. Clean the area with warm soapy water first, gently remove the crusts, then apply the cream. It’s that simple. If the infection is widespread, or if it’s bullous impetigo, oral antibiotics like cephalexin are needed. A typical dose for a child is 25-50 mg per kg of body weight, split into two or three doses a day for seven days.

Cellulitis almost always requires oral or IV antibiotics. For mild cases, cephalexin or dicloxacillin - both penicillin derivatives that resist the penicillinase enzyme - are standard. But here’s where things get tricky: in many places, over half of staph infections are now methicillin-resistant (CA-MRSA). That means cephalexin won’t work. The Infectious Diseases Society of America now recommends doxycycline or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) as first-line for suspected MRSA. These work against resistant strains and have cure rates of 85-90%.

For severe cellulitis - if you’re sick, have a high fever, or the infection is spreading fast - you’ll likely end up in hospital on IV antibiotics like cefazolin. And yes, it’s painful. But it’s life-saving. About 5-9% of cellulitis cases lead to bacteria entering the bloodstream (bacteremia), and 0.3% turn into necrotizing fasciitis - the so-called ‘flesh-eating’ infection. Early antibiotics stop that.

Who’s at Risk - And Why Age Matters

Impetigo loves children. About 75% of cases are in kids aged 2 to 5. Crowded places like daycare centers and schools are breeding grounds. In tropical regions, up to 20% of children get it each year. In Australia, outbreaks spike in summer when kids are barefoot and sweaty, and skin breaks more easily.

Cellulitis is an adult problem. The average age is 55. Why? Because as we age, our skin thins, circulation slows, and conditions like diabetes, obesity, or leg swelling (venous insufficiency) become common. Diabetes raises your risk of cellulitis by over three times. Obesity? That’s a 2.7-fold increase. Even a small cut on a diabetic foot can turn into a hospital stay. That’s why foot checks are part of every diabetes care plan.

Children with eczema or tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) are also at higher risk. The broken skin from itching gives bacteria an open door. That’s why treating fungal infections early is just as important as cleaning a cut.

Prevention: Simple Steps That Actually Work

There’s no magic bullet, but a few everyday habits cut infection risk dramatically:

- Wash hands and skin regularly, especially after playing outside or touching pets.

- Don’t share towels, clothing, or bedding if someone in the house has impetigo.

- Clean even small cuts with soap and water, then cover them with a bandage.

- Treat athlete’s foot fast - antifungal cream, not just foot powder.

- Keep fingernails short, especially in kids. Scratching breaks skin.

- In outbreaks, use antibacterial soap for a few days. It’s not overkill - it’s prevention.

For kids with recurrent impetigo, doctors sometimes recommend nasal mupirocin ointment for a week. Staph lives in the nose. If it’s there, it keeps coming back to the skin. Erase it from the nose, and you break the cycle.

When to See a Doctor - And What Not to Do

Don’t try to ‘wait it out’ with home remedies. Honey, tea tree oil, or vinegar soaks won’t kill staph or strep. They might soothe, but they won’t cure. If you see a honey-colored crust, redness that’s spreading, or a child who’s feverish and irritable - see a doctor. Diagnosis is usually visual. No lab test is needed unless the infection isn’t improving or there’s an outbreak.

Don’t squeeze or pick at the sores. That spreads bacteria to other parts of the skin. Don’t send a child with impetigo to school until they’ve been on antibiotics for at least 24 hours. That’s the rule in Australia, the U.S., and the UK. It’s not about being ‘safe’ - it’s about stopping transmission.

And never stop antibiotics early, even if the skin looks fine. Stopping after three days because it ‘feels better’ is how resistant strains survive and spread. Finish the full course - seven days for impetigo, five to 14 for cellulitis.

What’s Next? Faster Tests and Smarter Antibiotics

Right now, doctors guess the bacteria based on how the infection looks. But new tools are coming. The NIH is funding research into point-of-care tests that can identify staph, strep, and even MRSA in under 30 minutes - using just a swab from the sore. That means the right antibiotic on the first visit, not a trial-and-error approach.

Topical retapamulin (Altabax) is already approved in Australia and the U.S. for impetigo. It’s newer than mupirocin and works against resistant strains. Studies show 94% cure rates in kids. It’s pricier, but for recurrent cases or where resistance is high, it’s worth it.

And there’s growing pressure on doctors to stop prescribing antibiotics for minor rashes that aren’t bacterial. Many ‘skin infections’ are actually eczema flare-ups or viral rashes. Overuse fuels resistance. The American Academy of Dermatology now trains clinicians to say ‘no’ more often - and to treat the real cause, not just the redness.

Comments

Gloria Parraz

Finally, someone breaks down the difference between impetigo and cellulitis without using textbook jargon. I’ve seen so many parents panic over a scab, only to find out it’s just a harmless crust. This post saved me a trip to the ER last summer when my nephew had that honey-colored crust around his nose. Mupirocin worked like magic. No antibiotics needed.

December 18, 2025 at 09:10

pascal pantel

Let’s be real - the penicillin myth persists because lazy clinicians still use outdated guidelines. 90% of impetigo is S. aureus with penicillinase? That’s not new. It’s been documented since 2003. The fact that you still see penicillin prescribed is a failure of medical education, not a knowledge gap. Mupirocin is first-line. Period. If your local doc doesn’t know that, they’re practicing in 1998.

December 20, 2025 at 06:44

Nicole Rutherford

Who funded this? Big Pharma? They’re pushing mupirocin because it’s expensive. Why not just use salt water? Or tea tree oil? I read a study - not the one you quoted - that says natural remedies work better and don’t create superbugs. Also, why are they always talking about kids? What about adults with eczema? No one mentions that.

December 21, 2025 at 08:18

Dorine Anthony

My mom had cellulitis after a spider bite. She was in the hospital for five days. IV antibiotics, fever, the whole nightmare. I never realized how fast it spreads until I saw the photos. This post made me understand why they were so scared. Thanks for the clarity.

December 22, 2025 at 09:06

Sahil jassy

Good info. I live in India and we see this all the time. Kids with impetigo in school. No one cares. They just say 'it's just skin'. But it spreads like fire. Mupirocin is not available cheap here. We use neomycin cream. Works okay. But yes, stop sharing towels.

December 23, 2025 at 10:40

Chris Clark

Wait so if you got MRSA and your doc gives you cephalexin... you're basically just feeding the beast? That's wild. I thought all antibiotics were just 'kill bacteria'. Didn't know they had different targets. So doxycycline is the new hero? Makes sense. I’ve been taking it for acne anyway. Guess it’s a two-for-one.

December 25, 2025 at 06:25

William Storrs

Don’t let fear of resistance stop you from treating infections. If you’ve got redness spreading, fever, pain - get help. Antibiotics aren’t the enemy. Ignorance is. I’ve seen too many people wait until it’s too late because they were scared of ‘overusing’ meds. You don’t save the planet by letting bacteria win.

December 25, 2025 at 08:12

Janelle Moore

Did you know the government is using this to push vaccines? They’re calling it ‘bacterial resistance’ to scare parents into giving their kids more shots. Skin infections have always been normal. My grandma just used garlic. No antibiotics. No problems. Now they want to poison us with mupirocin and ‘retapamulin’ - sounds like a chemical weapon. This is all a lie.

December 26, 2025 at 16:06

Kathryn Featherstone

I’m a nurse and I see this every day. The biggest mistake? Parents stopping antibiotics after 3 days because ‘it looks better’. Then it comes back worse. And they blame the doctor. This post nails it - finish the course. Always. Even if it feels fine. The bacteria aren’t done.

December 27, 2025 at 00:21

Sajith Shams

Impetigo is just a sign of poor hygiene. Why are we treating it like it’s a medical mystery? Wash hands. Cut nails. Stop letting kids touch everything. No need for expensive creams. Basic sanitation solved 90% of this 50 years ago. Modern medicine overcomplicates everything.

December 28, 2025 at 12:24

Chris porto

It’s interesting how we treat skin like it’s separate from the body. But the skin is our largest organ. It’s the first line of defense. When it breaks, it’s not just a wound - it’s a doorway. The real question isn’t which antibiotic, but why did the barrier fail? Stress? Diet? Sleep? Maybe we should look upstream.

December 29, 2025 at 21:07

William Liu

This is exactly the kind of info we need more of. No fluff, just facts. I used to think cellulitis was just a bad rash. Now I know it’s a silent emergency. I’m sharing this with my whole family. Thank you.

December 31, 2025 at 03:30

Ryan van Leent

Why are we even using antibiotics for this? It’s not like the body can’t handle it. I had impetigo as a kid and it cleared up in a week without anything. You people are too scared of germs. Let nature take its course. Stop overmedicalizing everything.

January 1, 2026 at 16:06

Henry Marcus

Wait - so you’re telling me the government, the CDC, the WHO, Big Pharma, AND the American Academy of Dermatology are all in on this? They’re lying about penicillin resistance to sell mupirocin? And they’re hiding the fact that MRSA is a bioweapon developed in a lab? I’ve seen the documents. The ‘honey crust’? That’s not bacteria - it’s a chemical residue from 5G towers. You think this is about skin? It’s about control.

January 2, 2026 at 03:15