Every year, millions of people take multiple medications - some for chronic conditions, others for short-term symptoms. But what if the real danger isn’t just the drugs themselves, but how your genes react to them? That’s where pharmacogenomics comes in. It’s not science fiction. It’s happening right now in hospitals and clinics, changing how doctors decide which drugs to prescribe and at what dose - especially when drug interactions could turn deadly.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than You Think

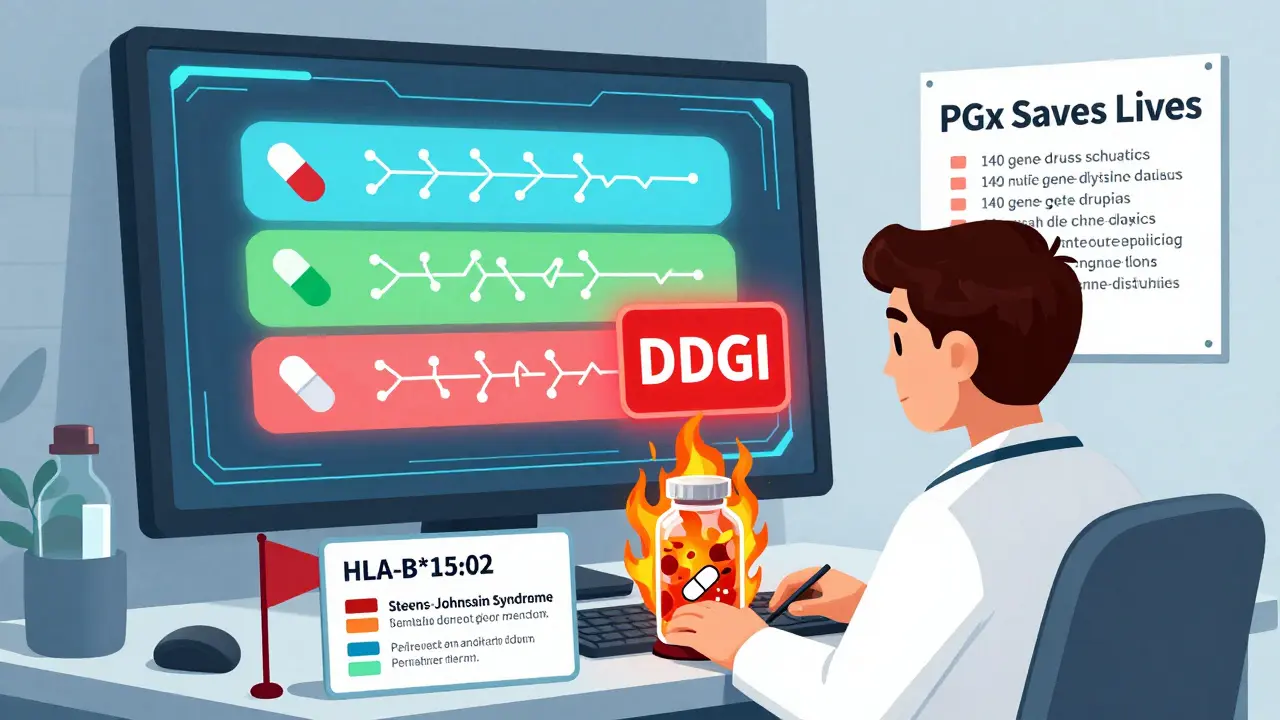

Most drug interaction checkers only look at what pills you’re taking. They don’t ask: What’s in your DNA? That’s a huge blind spot. Two people can take the exact same combination of medications, but only one suffers a severe reaction. Why? Because of genetic differences that affect how your body breaks down drugs. The key players here are enzymes like CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. These are your body’s natural drug processors. Some people have genes that make these enzymes work super fast - they clear drugs too quickly, making treatments ineffective. Others have genes that barely work at all - so drugs build up to toxic levels. For example, if you’re a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer and take codeine, your body can’t convert it to morphine properly. You get no pain relief. But if you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer? You could turn a normal dose into a lethal overdose without knowing it. The FDA lists over 140 gene-drug pairs with clear clinical implications. One of the most serious is HLA-B*15:02. If you carry this gene variant and take carbamazepine (a common seizure and bipolar medication), your risk of developing Stevens-Johnson Syndrome - a life-threatening skin reaction - jumps by 50 to 100 times. That’s not a small risk. That’s a red flag.How Drug Interactions Get Worse Because of Your Genes

Drug interactions don’t just happen between two pills. They get complicated when your genes are in the mix. This is called a drug-drug-gene interaction (DDGI). There are three main ways this plays out:- Inhibitory interactions: One drug blocks the enzyme that breaks down another. For example, fluoxetine (an antidepressant) slows down CYP2D6. If you’re already a slow metabolizer genetically, this can push you into dangerous drug buildup.

- Induction interactions: One drug speeds up enzyme activity. Rifampin, used for tuberculosis, can make your body clear warfarin too fast, increasing your risk of clots.

- Phenoconversion: This is the sneaky one. A drug temporarily changes how your genes behave. Say you have a gene that makes you a fast metabolizer of CYP2D6. But you start taking a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor like paroxetine. Suddenly, your body acts like a slow metabolizer - even though your genes haven’t changed. Your doctor has no way of knowing this unless they test your genetics.

Where It Matters Most: Antidepressants, Painkillers, and Antipsychotics

Some drug classes are far more likely to cause gene-driven problems. Antidepressants like SSRIs, painkillers like codeine and tramadol, and antipsychotics like risperidone all rely heavily on CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. If you’re on multiple medications for depression, anxiety, and chronic pain - common in older adults - your risk multiplies. Take the case of a 68-year-old woman on sertraline (an SSRI), tramadol (for arthritis pain), and metoprolol (for high blood pressure). Standard interaction checkers might flag sertraline and tramadol as a moderate risk. But if she’s a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer, tramadol becomes a serotonin syndrome time bomb. Sertraline blocks CYP2D6, and her genes already slow down tramadol breakdown. The result? Too much serotonin, too fast - shaking, fever, confusion, even death. This isn’t theoretical. At Mayo Clinic, where they’ve been testing patients’ genes before prescribing since 2011, 89% of patients had at least one gene-drug interaction that could have caused harm. Clinical alerts based on genetics cut inappropriate prescribing by 45%.

The Gap Between Science and Practice

Here’s the problem: we have the science. We have the guidelines. But most doctors and pharmacists aren’t using it. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has published over 100 evidence-based guidelines for gene-drug pairs. But only 22% of the FDA’s listed gene-drug associations have these formal guidelines. That means for a lot of drugs, doctors are flying blind. Even worse, only 15% of U.S. healthcare systems have PGx data integrated into their electronic health records. Most pharmacies still use old drug interaction databases like Lexicomp - which ignore genetics entirely. A 2023 survey of 1,200 pharmacists found only 28% felt trained to interpret genetic results. And 67% said their systems didn’t even show them the data. It’s not just about knowledge. It’s about infrastructure. Setting up a PGx program costs an average of $1.2 million per hospital. Reimbursement is a mess - only 19 CPT codes exist for PGx testing, and insurers often pay $250-$400 per test, which doesn’t cover the cost of interpretation and follow-up.Who’s Getting It Right - And Who’s Falling Behind

Some institutions are leading the way. Vanderbilt’s PREDICT program has tested over 100,000 patients since 2011. They’ve shown that preemptive testing reduces hospitalizations for adverse drug reactions by nearly 30%. Mayo Clinic’s system automatically flags risky prescriptions before they’re filled - and doctors follow the alerts 80% of the time. But community hospitals? Only 8% offer any kind of PGx testing. And the biggest gap? Diversity. Over 98% of pharmacogenomics research participants are of European or Asian ancestry. African populations make up just 2% - even though they have higher rates of certain gene variants like CYP2D6*17, which changes how codeine works. That means guidelines based on current data may not work for everyone. And that’s dangerous.

Comments

Jessica Salgado

I had no idea my genes could turn a simple painkiller into a death sentence. My grandma took codeine for years after her hip surgery and never said a word about it being weird. Now I’m scared to even look at my own 23andMe report. What if I’m one of those ultra-rapid metabolizers and I’ve been silently poisoning myself? I’m gonna call my pharmacist tomorrow.

Also, why isn’t this standard before prescribing anything? This feels like we’re driving a car without checking the engine first.

December 17, 2025 at 01:19

amanda s

Oh here we go again with the gene nonsense. You think your DNA is the reason you can’t handle ibuprofen? Maybe you just have a weak stomach and a bad diet. I’ve been on 12 meds at once since I was 30 and I’m fine. This is just Big Pharma’s way of selling you another $500 test so they can charge you more later. Wake up, sheeple.

Also, who lets a 68-year-old woman take tramadol AND sertraline? That’s not genetics, that’s medical malpractice. Blame the doctors, not your genes.

December 17, 2025 at 19:38

Peter Ronai

Oh wow. A 90.7% increase in detected interactions? That’s not because the science is good - it’s because the old systems were garbage. Of course they missed everything. Lexicomp is basically a 2005 Excel sheet with a fancy UI.

And let’s not pretend this is new. I’ve been reading CPIC guidelines since 2016. The fact that 67% of pharmacists don’t even see the data? That’s not ignorance - that’s institutional laziness. Your EHR vendor doesn’t want to integrate PGx because it would require them to fix their broken APIs. And your hospital won’t spend $1.2M because they’d rather pay for ER visits than prevent them.

Also, 98% of research is on Europeans? Yeah, because nobody funds studies on African populations unless it’s for HIV. This isn’t science - it’s colonialism with a lab coat.

December 18, 2025 at 10:02

Michael Whitaker

While the empirical evidence supporting pharmacogenomic integration into clinical workflows is undeniably compelling, one must consider the epistemological limitations of current genetic databases. The reliance on CYP polymorphisms as primary biomarkers represents a reductionist paradigm that fails to account for epigenetic modulation, gut microbiome interactions, and polygenic risk scores.

Furthermore, the assertion that ‘the technology is ready’ is premature. Without standardized ontologies for genomic data interoperability across EHR systems - and without mandatory continuing education for prescribers - any implementation remains a performative gesture rather than a systemic intervention.

One might even argue that the current discourse around PGx functions as a neoliberal technofix, diverting attention from structural failures in pharmaceutical regulation and healthcare access.

December 19, 2025 at 11:41

Sachin Bhorde

Bro this is legit game changer. I work in a clinic in Delhi and we just started doing CYP2D6 tests for pain patients on tramadol. Crazy how many were poor metabolizers and just got no relief - or worse, got sick. We got a 40% drop in side effects in 3 months. Also, 23andMe is useless for Indians - most variants they test are Euro-centric. We need local data. Like, CYP2D6*17 is common in South Asians but they don’t even list it on their reports.

And yeah, docs here don’t know squat about PGx. But if you bring the report, they at least shut up and listen. Just show them the paper. Simple.

Also, if you’re on 5+ meds, get tested. It’s like getting a car tuned - except your body’s the engine.

December 19, 2025 at 21:02

Joe Bartlett

My mate got prescribed fluoxetine and then warfarin. He bled out of his gums for a week. Turns out he’s a slow CYP2D6 metabolizer and fluoxetine blocked the enzyme. They didn’t test his genes. He was lucky. Now he’s on a different pill. Simple as that.

Why isn’t this done everywhere? It’s not hard. It’s just not prioritised.

December 20, 2025 at 01:54

Marie Mee

They’re lying about the 140 gene-drug pairs. I read somewhere that the FDA hides the real numbers because they don’t want people to panic. And what about the 23andMe reports? They’re just giving you data so you’ll go to the doctor and get more tests and more meds. They want you dependent. They don’t care if you live or die - they care about the profit margin.

Also, why do they only test rich people? My cousin in Texas got tested. I asked for mine and they said ‘it’s not covered.’ That’s not science. That’s capitalism.

December 20, 2025 at 09:06

Naomi Lopez

It’s fascinating how the entire paradigm of pharmacotherapy is being redefined by a single layer of biological data - yet we continue to treat genetic results as static, deterministic inputs rather than dynamic, context-sensitive variables within a complex physiological ecosystem.

Consider that phenotypic expression is modulated by environmental factors - diet, stress, circadian rhythm - none of which are accounted for in current PGx algorithms. The notion that a single SNP can reliably predict clinical outcomes is, frankly, an oversimplification bordering on scientism.

That said, the clinical utility in polypharmacy populations remains compelling. I’d argue for tiered implementation: prioritize high-risk drug classes and high-risk patient cohorts before scaling universally.

December 21, 2025 at 16:29