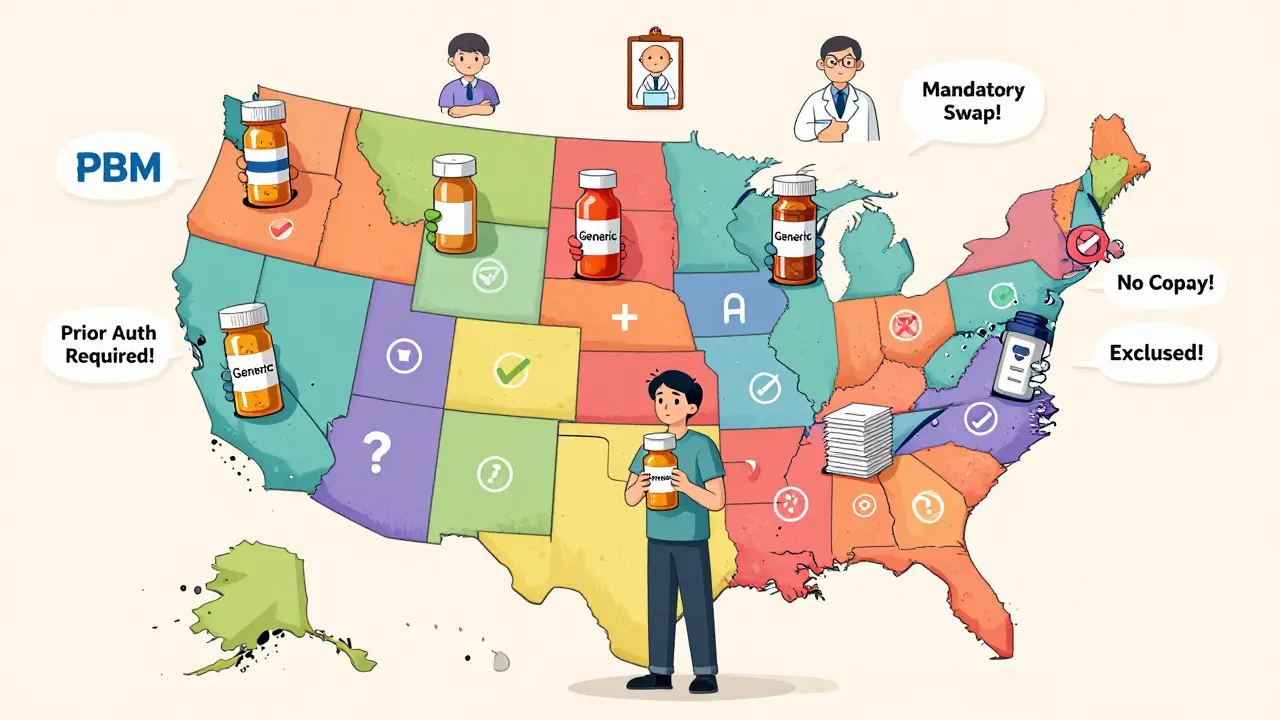

When you’re on Medicaid, getting your prescriptions filled shouldn’t be a maze. But if you’ve ever tried to refill a generic medication across state lines, you know it’s anything but simple. One state might let your pharmacist swap a brand drug for a cheaper generic without a second thought. Another might require your doctor to jump through five hoops before approving the same pill. The truth? Medicaid generic coverage isn’t national-it’s a patchwork of 51 different systems (50 states + DC), each with its own rules, limits, and surprises.

What Gets Covered-and What Doesn’t

Federal law doesn’t force states to cover prescription drugs under Medicaid. But every single state does. Why? Because without drug coverage, people skip doses, end up in the ER, and cost the system more in the long run. So all states cover outpatient generics, but what’s in that coverage? Not everything. The Affordable Care Act says states must cover any drug made by a manufacturer that’s signed up for the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. That covers over 90% of generic drugs on the market. But there are hard exclusions. Fertility drugs, weight-loss pills, erectile dysfunction meds, and cosmetic treatments? Not covered anywhere. Colorado’s Health First Colorado program lists these clearly. So if your doctor prescribes a weight-loss drug, Medicaid won’t pay for it-no matter how medically necessary it feels. Even within covered drugs, states decide which ones are preferred. Think of it like a playlist: some songs get top billing, others get buried. States build Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) that rank generics by cost, safety, and clinical evidence. If your drug isn’t on the list, you might need prior authorization-or pay more out of pocket.Generic Substitution: Mandatory or Optional?

Here’s where things get messy. In at least 41 states, pharmacists are legally required to substitute a generic for a brand-name drug if it’s rated as therapeutically equivalent by the FDA. That’s automatic. But not all states do it the same way. In Colorado, the law says the generic must be dispensed unless the prescriber writes “Dispense as Written” or the brand is actually cheaper. In California, pharmacists can swap generics without notifying the doctor. But in 12 states, pharmacists need to tell the prescriber before swapping. And in 28 states, they must document why the substitution was made. Why does this matter? Because if your doctor prescribed a specific brand for a reason-maybe you had a reaction to a different generic last year-and your pharmacist swaps it without telling anyone, you could end up with side effects or a flare-up. That’s why some states require documentation. Others don’t. It’s not about safety-it’s about paperwork.Prior Authorization: The Hidden Bureaucracy

You might think if a drug is generic, it’s easy to get. Not always. Many states use prior authorization (PA) to control use-even for generics. Why? Because some generics are expensive. Others are used for conditions that require strict oversight, like opioids or psychiatric meds. In Colorado, if your drug is on the “Non-Preferred” list, you need PA. For opioids, the rules are tighter: first-time prescriptions are limited to a 7-day supply, and you can’t get more than 8 doses per day. In Texas, PA is rare for generics-but common for brand-name drugs. In contrast, Massachusetts has minimal PA for generics, while Mississippi requires it for almost everything. The process isn’t quick. In the best cases, like Colorado, you get a decision within 24 hours. In others, it can take up to three days. And if you’re a doctor? You’re spending 15 minutes per patient just filling out forms. That’s over $8,200 a year in lost time per physician, according to the American Medical Association.

Copays: How Much You Pay Out of Pocket

Even with Medicaid, you might still pay something. Copays for generics vary wildly. For beneficiaries earning up to 150% of the federal poverty level, most states allow up to $8 per prescription for non-preferred generics. But many charge less-or nothing at all. In Vermont, copays for generics are $0. In New York, they’re $1 for preferred generics and $3 for non-preferred. In Florida, you pay $5. But in some states, if your income is below 100% of the poverty line, you pay nothing-even for non-preferred drugs. Here’s the catch: if your drug isn’t on the state’s preferred list, your copay goes up. And if you’re on Medicare Extra Help (which you can qualify for if you have Medicaid), you can switch your drug plan once a month. That means you might need to re-negotiate your coverage every time you change plans.Step Therapy: Try This First

Step therapy is when you have to try one drug before moving to another-even if your doctor says the first one won’t work. It’s common in states with tight budgets. Thirty-two states use step therapy for certain drug classes like pain meds, antidepressants, or asthma inhalers. In Colorado, for certain gastrointestinal conditions, you have to fail three preferred proton pump inhibitors and all preferred NSAIDs before they’ll approve a more expensive generic. That’s not just bureaucracy-it’s clinical decision-making. But in California, step therapy is rare for generics. The difference? Cost. States with higher Medicaid spending can afford to be more flexible. The problem? A 2024 University of Pennsylvania study found that when Medicaid patients get switched mid-treatment due to step therapy denials, hospital admissions rise by 12.7%. That’s not just inconvenient-it’s dangerous.

Who’s Running the Show? PBMs and Formularies

You might think the state runs the pharmacy program. But most states outsource it to Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)-companies like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx. These three manage Medicaid pharmacy benefits in 37 states as of early 2025. That means your formulary (the list of covered drugs) might look the same in Ohio and Indiana, even though they’re different states. But the rules? Still different. One PBM might require PA for a generic that another doesn’t. One might allow pharmacist substitution, another won’t. It’s confusing. And it’s intentional. PBMs negotiate rebates with drugmakers. States rely on those rebates to keep costs down. But when rebates drop-like if Congress passes a bill to remove inflationary rebates on generics-states scramble. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that could cost states $1.2 billion a year. That’s not a small hit. It means higher copays, fewer covered drugs, or both.What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

Big changes are coming. In December 2024, CMS proposed a rule requiring all Medicaid programs to cover anti-obesity medications. If it passes, it would be the biggest expansion of covered drugs since the Affordable Care Act. That could affect nearly 5 million people. At the same time, the Medicare Two Dollar Drug List Model-where Part D plans offered generics for $2-was discontinued in March 2025. But the data from that pilot showed something important: when generics are cheap and easy to get, adherence goes up by 18.4%. States are watching. Michigan’s value-based purchasing pilot for diabetes drugs cut costs by 11.2% without hurting adherence. That’s a model others are considering. By 2027, Medicaid will likely see 87.2% of all pharmacy claims filled with generics-up from 84.7% today. That’s good news for cost control. But it also means more pressure on supply chains. In 2024, the FDA listed 17 generic drugs used in Medicaid as being in short supply. If a key generic disappears, patients get stuck. No backup. No easy fix.What This Means for You

If you’re on Medicaid, here’s what you need to do:- Know your state’s Preferred Drug List. Ask your pharmacist or visit your state’s Medicaid website.

- Ask if your generic is preferred. If it’s not, you might pay more or need PA.

- Keep a list of your meds and why you’re on them. If your pharmacist swaps your drug, you’ll need to tell your doctor.

- If you’re denied a drug, appeal. Most states have a fast-track process.

- If you’re switching from Medicare Part D to Medicaid (or vice versa), update your drug plan immediately. You can change once a month.

Are all generic drugs covered by Medicaid in every state?

Yes, all 50 states and DC cover outpatient generic drugs under Medicaid. But not every generic is automatically approved. States use Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) to prioritize certain generics based on cost and clinical effectiveness. If a generic isn’t on the preferred list, you may need prior authorization or pay a higher copay.

Can my pharmacist switch my brand-name drug to a generic without asking me?

In 41 states, pharmacists are legally required to substitute a generic if it’s FDA-rated as therapeutically equivalent. But they must follow state rules. Some states require them to notify your doctor, others don’t. In Colorado, substitution is mandatory unless the prescriber writes “Dispense as Written” or the brand is cheaper. Always check your state’s pharmacy laws.

Why do I need prior authorization for a generic drug?

Even though generics are cheaper, some are still expensive-or used for conditions that require careful control, like opioids or psychiatric drugs. States use prior authorization to prevent overuse and ensure the drug is medically necessary. For example, Colorado requires PA for non-preferred generics and limits opioid prescriptions to 7 days for first-time users.

How much can I be charged for a generic drug under Medicaid?

States can charge up to $8 per prescription for non-preferred generics if your income is at or below 150% of the federal poverty level. Many states charge less-$1 to $5-or nothing at all for low-income enrollees. Preferred generics often have lower copays. Check your state’s Medicaid website for exact amounts.

What if my generic drug is on backorder or unavailable?

If your generic is out of stock, your pharmacist should contact your prescriber to switch to another FDA-approved generic in the same class. If no alternatives are available, your provider can request an exception from Medicaid. In cases of critical shortages, states may temporarily waive prior authorization or step therapy requirements. Keep a backup list of your meds and contact your state Medicaid office if you’re denied access.

Do Medicaid and Medicare Part D work the same for generics?

No. Medicare Part D plans vary widely in coverage and copays for generics. Only 20% of Part D enrollees had access to $2 generic plans under the discontinued Two Dollar Drug List Model. Medicaid has more consistent coverage, but state rules differ. If you qualify for both programs, you can change your Part D plan once a month to better align with your Medicaid benefits.

Can I appeal if Medicaid denies coverage for a generic drug?

Yes. All states have an appeals process. You or your provider can submit a written request explaining why the drug is medically necessary. Many states require a decision within 72 hours for standard appeals and 24 hours for urgent cases. If denied, you can request a second-level review. Some states offer fast-track appeals for life-sustaining medications.

Why do some states have better formulary clarity than others?

Formulary clarity depends on how states manage their pharmacy benefits. States like Massachusetts rate high in provider satisfaction (4.6/5) because they publish clear, updated PDLs online with easy search tools. Others, like Mississippi, rate lower (2.8/5) due to outdated lists, confusing language, or lack of online access. Better clarity reduces errors, saves time for providers, and improves patient outcomes.

Comments

Betty Bomber

Just had to fight my pharmacy for a generic blood pressure med. They swapped it without telling me, and I ended up with dizziness for a week. No one warned me. States need to mandate notifications. This isn't just paperwork-it's safety.

January 27, 2026 at 16:25

Sally Dalton

OMG YES THIS. I'm in Texas and my pharmacist just handed me a different generic for my antidepressant and I had no idea until I read the label. I cried in the parking lot. Why does it feel like our meds are a game of musical chairs?? 😭

January 28, 2026 at 14:19

Ashley Porter

The PBM-driven formulary fragmentation is a classic principal-agent problem. States outsource regulatory authority to third-party entities whose incentives are misaligned with patient outcomes, resulting in suboptimal therapeutic alignment and increased administrative burden. The lack of transparency in rebate structures exacerbates this inefficiency.

January 29, 2026 at 14:12

eric fert

Let me get this straight-states are spending millions on prior auth forms so they can save a few bucks on generics, but when a patient gets hospitalized because they couldn't get their med on time, suddenly it's 'unforeseen consequences'? That's not fiscal responsibility, that's systemic cruelty dressed up as budgeting. And don't even get me started on how PBMs pocket the rebates while patients get stuck with the side effects. We're not fixing healthcare. We're just repackaging greed.

January 31, 2026 at 06:22

Angie Thompson

My grandma in Florida got her $0 generic copay last month and finally started taking her meds regularly. She says she feels like a person again, not a statistic. 🙏 If we can make generics affordable, we can save lives. Why is that so hard?

January 31, 2026 at 23:36

bella nash

It is not merely a matter of pharmaceutical policy but a reflection of the ontological disjunction between state sovereignty and the universal right to health. The fragmentation of Medicaid formularies constitutes a de facto denial of equitable access under the guise of fiscal prudence. The absence of federal standardization is not an oversight-it is an ideological choice.

February 1, 2026 at 13:02

George Rahn

Let’s be real: America doesn’t need 51 different Medicaid systems. We need one national standard. The fact that Colorado requires documentation for generic substitution while Mississippi demands prior authorization for aspirin is a national embarrassment. This isn’t federalism-it’s bureaucratic chaos engineered by lobbyists who profit from confusion. We’re not a patchwork country. We’re a nation. Act like it.

February 3, 2026 at 00:32

Mohammed Rizvi

Indian pharmacy system is way simpler: if it's generic, you get it. No forms, no waiting, no drama. But then again, we don't have PBMs billing $200 per hour for 'clinical review'. Maybe we should stop outsourcing common sense to corporations that don't even know your name.

February 4, 2026 at 07:47

Ryan W

Step therapy is a necessary cost-control mechanism. If you're going to prescribe expensive meds, you better prove it's not just because you're lazy. The AMA whining about 15 minutes per patient? That's their inefficiency, not the system's fault. Stop blaming the rules and fix your workflow.

February 4, 2026 at 07:50

Geoff Miskinis

One cannot help but observe the tragicomic absurdity of a system where a $0.02 generic pill requires a 72-hour bureaucratic odyssey to access, while a $12,000 branded drug is approved in minutes. This is not healthcare. This is performance art for actuaries.

February 4, 2026 at 17:18

Curtis Younker

You guys are right-it’s messed up. But here’s the good news: you can fight it. I helped my neighbor appeal her denial last month. Took 3 days, one phone call to her doctor, and a handwritten letter. She got her med. You don’t have to just accept it. Speak up. File the appeal. You’ve got more power than you think.

February 6, 2026 at 16:41

Shawn Raja

They say Medicaid is a safety net. But when your safety net has 51 different holes, each with its own rules, and your pharmacist is legally allowed to swap your meds without telling you-what are you really safe from? The system isn’t broken. It was designed this way. To keep you confused. To keep you quiet. To keep you paying the price in pain, not dollars.

February 7, 2026 at 06:31